Dear friends,

We talked in the last chapter about ‘pan-millenialism,’ the belief that it will all pan out in the end. That perspective gets even more attractive when you reach Revelation 20 where, as we will see, the dominant perspective among preachers in my context is ‘amillennialism,’ the belief that there will be no literal millennium.

When you read Revelation 20 at face value, it seems to be going another way, so there is a bit of explaining to do. Have a look at the text of Revelation 20:1-6.

And I saw an angel coming down out of heaven, having the key to the Abyss and holding in his hand a great chain. He seized the dragon, that ancient serpent, who is the devil, or Satan, and bound him for a thousand years. He threw him into the Abyss, and locked and sealed it over him, to keep him from deceiving the nations anymore until the thousand years were ended.

After that, he must be set free for a short time.

I saw thrones on which were seated those who had been given authority to judge. And I saw the souls of those who had been beheaded because of their testimony about Jesus and because of the word of God. They had not worshiped the beast or its image and had not received its mark on their foreheads or their hands.They came to life and reigned with Christ a thousand years. (The rest of the dead did not come to life until the thousand years were ended.) This is the first resurrection. Blessed and holy are those who share in the first resurrection. The second death has no power over them, but they will be priests of God and of Christ and will reign with him for a thousand years.

On the face of it there is a resurrection of the martyrs who reign with Christ for a thousand years, while Satan is locked and sealed in the Abyss so he can’t deceive the nations anymore.

But since Augustine that chronology has been widely questioned. Augustine saw the millennium as non-literal and as describing the time we are now in.

Now anyone who has felt like they have been in a spiritual battle with forces of evil it doesn’t feel like Satan (who the NT warns us is prowling around waiting to devour us) is safely locked away on a chain and sealed in wherever the Abyss is. It feels like he is a real and present enemy – working through and empowering all the Beastly adversaries, False Prophets and Great Prostitutes we keep coming across. So how can he be bound up and yet still active?

Let’s turn to some of the best articulators of the amillennial position for their defence.

Amillenialism

1. Augustine (4th–5th century)

Augustine is the foundational figure for classical amillennialism. He explicitly interprets Revelation 20 symbolically and identifies the millennium with the present church age. Augustine focuses in on the ‘binding of Satan’ which he suggests refers to his inability to stop the nations from believing the gospel. In the City of God (20.7) he states that, ‘The devil is bound… so that he should not seduce the nations which belong to Christ.’

Augustine’s Satan is still active in temptation and persecution, but restricted in scope, and the ‘millennium’ begins with Christ’s first coming, not a future earthly reign. This ‘binding’ of Satan in the Abyss explains why Gentile nations can now be converted, when that was impossible before Christ.

Anthony A. Hoekema (20th century)

The Dutch-American Calvinist Hoekema addresses the objection that Satan is obviously active today. He also sees the binding as functional and missional, not absolute, arguing that Revelation 20:3 suggests the scope of the binding is to limit Satan ‘so that he might not deceive the nations.’ He sees the millennium as a heavenly reign of Christ, not an earthly one

Hoekema states:

‘The binding of Satan does not mean that Satan can no longer tempt believers or attack the church. It means that he can no longer prevent the spread of the gospel among the nations.’

Hoekema also links Revelation 20 to Matthew 12:29 and Luke 10:18, where Jesus tells his disciples: ‘I saw Satan fall like lightning from heaven.’ So Christ bound Satan during his earthly ministry.

3. G. K. Beale (big fat commentary – NICNT)

Beale offers a bit more evidence for this through his literary and intertextual reading of Revelation. Basically he is into apocalyptic symbolism. He sees Revelation 20 as retelling earlier visions in the book. The ‘Abyss’ imagery as from OT and Jewish apocalyptic language, and meaning divine restraint, and like Augustine and Hoekema that the binding means Satan cannot deceive the nations corporately, though he still deceives individuals

Beale argues:

“Satan’s binding does not eliminate his activity but curtails his authority over the nations so that the gospel can spread.”

He also stresses that Revelation 12 already depicts Satan as cast down yet active, reinforcing the “defeated but dangerous” paradox.

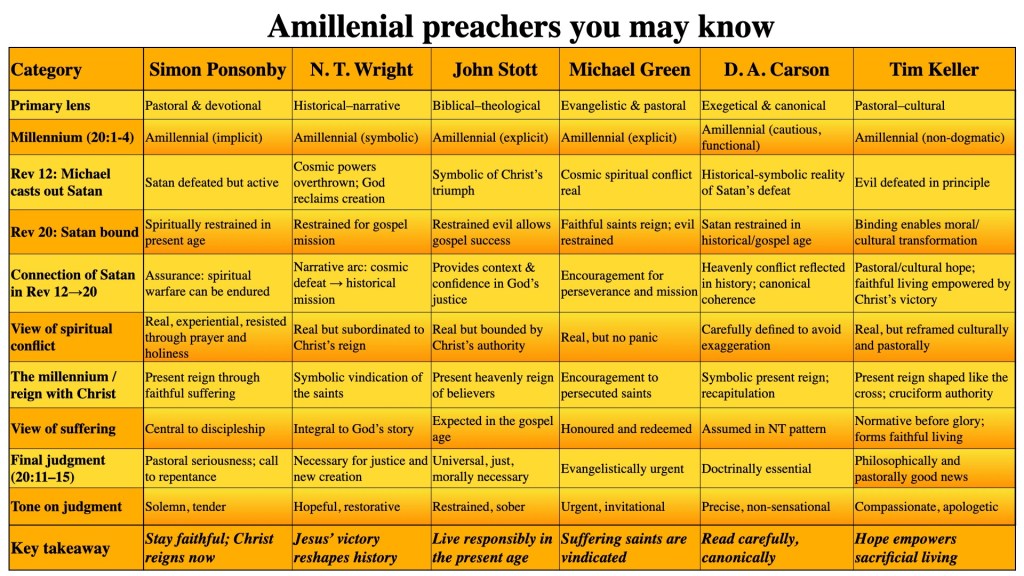

This view has shaped preachers you may know: Consider American evangelical thought leaders Don Carson and Tim Keller, Anglican Evangelical ‘fathers’ like John Stott and Michael Green, and contemporary preachers like Simon Ponsonby and NT Wright (both based in Oxford). With different priorities in interpreting they all pick up an implicit or explicit, symbolic or functional, amillennial position – with varying degrees of caution (and occasional tendency towards the aforementioned pan-millenialism!)

If you are going to be an amillennial you need to answer the question of what is the Abyss (if even when Satan is locked and sealed in it, he can still be a real and present danger). You also need to explain how the Abyss in Revelation 20 relates to the Abyss in Revelation 9 (from where demons are released to cause havoc). The weight of interpretation is put on the word ‘bound’ to make it mean that while Satan is (or isn’t) on a long chain he can still get out of the Abyss that the rest of the passage sounds like he has been sealed and locked into seems to be doing a lot of exegetical heavy lifting.

One of the appeals Beale and others make is to Second Temple Jewish literature. That sees the ‘abyss’ (Heb. tehôm, Gk. abyssos), not a fixed location with one function but as a cosmic realm. The place of chaos and demonic powers, that are held there by divine restraint. It picks up on images in Genesis and Psalms of primeval chaos before the creation of the world (Gen 1:2; Ps 74:13–14), the image in Isaiah of a subterranean prison (Isa 24:21–22) and defines the Abyss as a temporary holding places for evil spirits, distinct from final judgment. (see 1 Enoch 10:4–6, 18:11–16; Jubilees 5:6–10, 10:7-9, Testament of Levi and some Qumran material).

Augustine defines the Abyss by its function in Revelation 20: It is place in which Satan is bound “in order that he may not seduce the nations” (City of God 20.7).

So amillennials don’t read ‘locked and sealed’ literally for three reasons:

(1) The ἵνα ‘so that’ clause in Revelation 20:3 discusses above, means the binding is just about the gospel.

(2) Revelation regularly uses absolute sounding language symbolically. So Christ is described as ruling the nations with a rod of iron’ even while rebel; Saints ‘reign’ even while they suffer and die; Satan is ‘cast down in Revelation 12 even while he persecutes the church.

(3) Clear NT teaching demands ongoing satanic activity – Satan ‘prowls like a lion’ (1 Pet 5:8); he ‘schemes as our enemy’ (Eph 6:11); and he ‘deceives’ individuals (2 Cor 11:14).

So “locked and sealed” expresses certainty of God’s control, not total inactivity.

So on the basis that Scripture interprets Scripture, Revelation 20 cannot mean Satan is wholly inactive during the church age. So amillennialists have to reinterpret the imagery rather than contradict the wider canon.

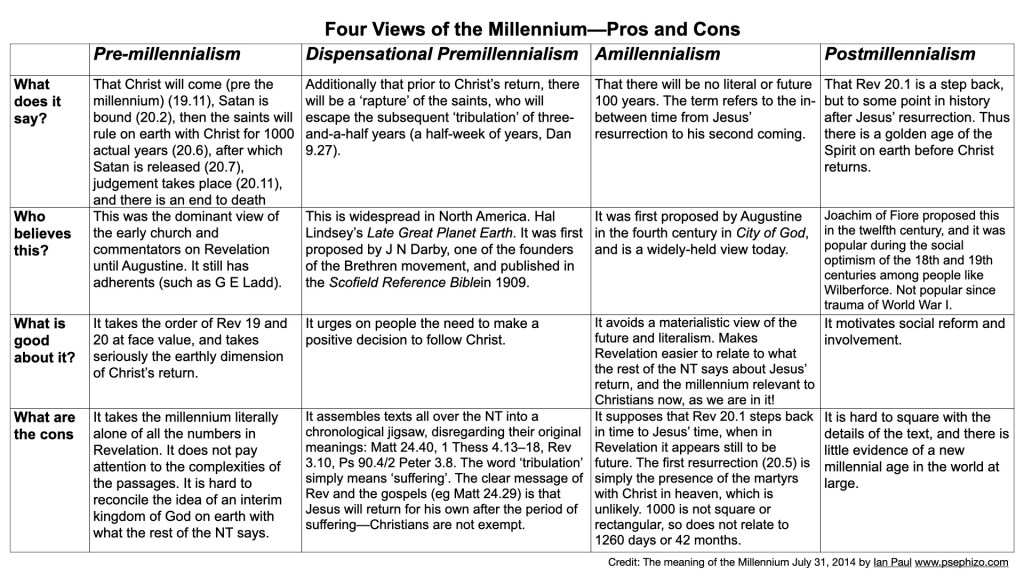

There are alternatives to amillennialism:

In his blog Ian Paul sums all this up as follows

In fact, none of these schemes is satisfactory, since they treat the millennium chronologically rather than theologically—they think that it is one event in a sequence, rather than being one way of explaining Jesus’ return set amongst other ways of understanding it. Rev 19–21 actually contains seven unnumbered visions, each of which starts with the phrase ‘And I saw…’ at Rev 19.11, 19.17, 19.19, 20.1, 20.4, 20.11, 21.1. As with other series in Revelation, we need to read them concurrently rather than sequentially, as giving a range of different insights into the meaning of Jesus’ return.

These visions will show:

- Justice will conquer (19.11)

- The Word will prevail (19.15)

- Deception will die (19.20, 20.10)

- The saints are vindicated (20.4)

- Heavens and earth will be remade (20.11, 21.1)

- Death will be no more (20.14, 21.4)

- God is present with his people (21.3, 21.16)

Ian points to Mike Gilbertson

Gilbertson argues

The millennium of Revelation 20 is a rich and powerful symbol with important implications for our understanding of God’s relationship with the world… long-established debates between the various traditional approaches to the text (premillennialism, postmillennialism, amillennialism) tend sometimes to obscure the theological significance of the passage.

Instead he sees the millennium:

‘not as the prediction of a literal future state, nor as a timeless abstraction… but as a symbol which conveys key truths about God’s plan to execute his justice and renew the world. The symbol is situated in the future, but has profound implications for how we live now.’

He concludes…

‘The biblical vision of the triumph of God, the lordship of Christ, God’s vindication of his people, and his commitment to transform the earth, provides the church with compelling resources to speak prophetically and relevantly in this contemporary context. The symbol of the millennium helps us to affirm profound hope for the present and the future in the light of the ultimate power of God’s love and justice.’

And, I have just been handed a dissertation on Jurgen Multmann’s eschatology by a friend. What was striking was that Moltmann did not want to dismiss the idea of a future millennium because as a German survivor of WWII he saw it as a future millennium as a real opportunity for Jew and Gentile church to be reconciled together. I’ll have to have a read of the Coming of God to check that out.

It will all pan out in the end… but I’ll give the last word to Ian Paul to try and inspire us not to check our brains at the door:

‘it is really time we got more excited about where the train is taking us!’ Ian Paul1

Read More:

The Lamb Wins Whole Series Catch Up : Introduction: Chp 1: Hope is Here | Chp 2: First, Love: Ephesus | Chp 3: Fear Not: Smyrna | Chp 4: I Know: Pergamum | Chp 5: Tolerate This: Thyatira | Chp 6: Wake Up: Sardis | Chp 7: Hold On: Philadelphia | Chp 8: Knock, Knock: Laodecia | Chp 9: What Must Soon Take Place | Chp 10: Holy Forever | Chp 11: Most Blessed | Chp 12: One That Was Slain | Chp 13: Come Home | Chp 14: Sun Forbear to Shine | Chp 15: 144000 | Chp 16 Sound of Silence | Chp 17: Spiralling Down | Chp 18 Two Witnesses | Chp 19 The Rapture | Chp 20 The Beast | Chp 21 False Prophet | Chp 22 Hallelujah | Chp 23 Millennium

Subscribe Below

If you have enjoyed this post why not check out somauk.org/stories and maybe even pay it forward by sharing the post and maybe take a moment to bless a brilliant charity? SOMA UK relies of the generosity of churches and supporters to fulfil our marvellous ministry – encountering God globally. Every donation goes a long way.

To support our ministry it’s www.somauk.org/donate