I recently gave a talk to some senior Anglican clergy where I included reference to a group called the Nonjurors. They were concientious objectors to the direction of travel in the Church in their day – over the issue of an oath of allegiance to the new monarch. As with much of history there are some interesting parallels to see our own era through… and some lessons to consider about a) their long-term survival and b) the late adopter of their cause who turned out to have a profound impact on global political and church history.

The Nonjurors were conviction Anglicans who refused to take the oaths of allegiance to William III and Mary II after the deposition of James II in the Glorious Revolution (1688–89).

These clergy numbered about 400 in England, 2% of the overall numbers, but included eight bishops and the archbishop of Canterbury, William Sancroft. They adopted a policy of nonresistance to the established authorities, and continued to be loyal to James II. From 1694 they maintained a separate ecclesiastical succession, but (as often happens with breakaway groups) they were divided – particularly over liturgical usages, and their numbers dwindled in the 18th century; the last Nonjuror bishop died in 1805.

But this story of a century of resistance, infighting and ultimate failure is not the whole of the story. Included among their number was one who was only an infant when they began their resistance. This contemporary of Newton , Locke and Woolman was not an early adopter of the Nonjuror resistance. In fact in 1705, he entered Emmanuel College , Cambridge , and became a fellow in 1711. He planned to enter the priesthood of the Church of England, but in 1714, at the death of Queen Anne he found himself unable to take the required oath of allegiance to the German speaking George I as lawful ruler of the United Kingdom, and was accordingly ineligible to serve as a university teacher or parish minister. His red lines had (finally) been crossed. He became a second generation Nonjuror.

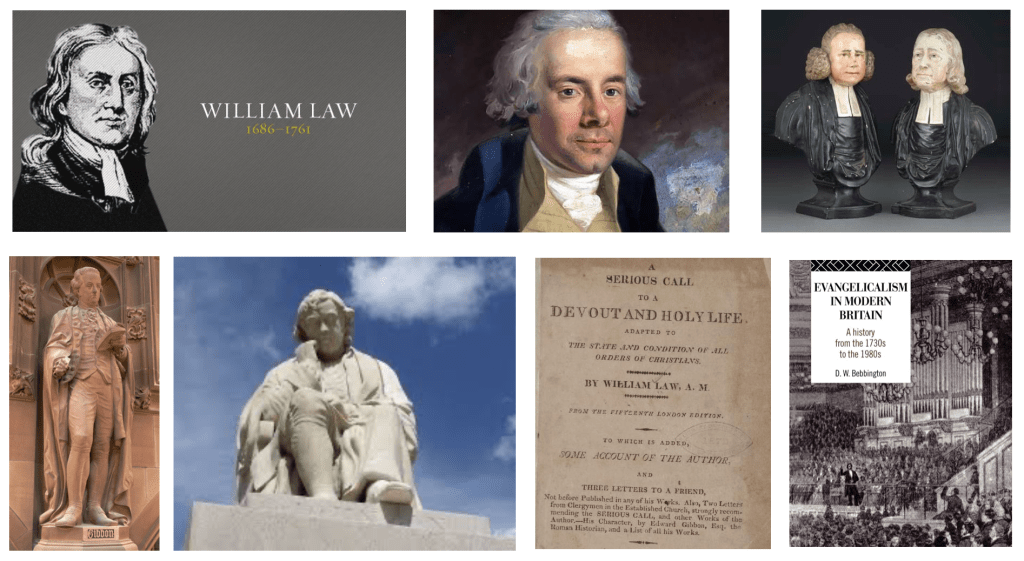

For William Law his conscience meant losing his position at Emmanuel College, Cambridge. It also meant giving up on all prospects of parish ministry. So into exile he went, where he became a private tutor to the family of the renowned historian Edward Gibbon, and preached through his books. Among the books was the 1729 work A Serious Call To a Devout and Holy Life a book that changed history. The thesis is that God does not merely forgive our disobedience, he calls us to obedience.

His personal integrity and writing, greatly influenced the evangelistic movement of his day. John Wesley probably read William Law’s works in the early 1730s (although if you read Wesley’s A Plain Account it sounds like he read them before they were written/published!). He spent time with Law before his famous 1733 semon ‘Circumcision of the Heart‘ and was undoubtedly deeply impacted by him. From the mid-1740s he republished A Serious Call in multiple editions, eventually calling William Law ‘Our John the Baptist’. These reprints had a profound effect on many including in 1784 William Wilberforce (1759–1833). Wilberforce the politician, philanthropist, and leader of the movement to stop the slave trade, was deeply touched A Serious Call. Law even had an impact on Enlightenment thinkers such as the writer Samuel Johnson and on his employer Edward Gibbon.

Samuel Johnson

“I became a sort of lax talker against religion, for I did not think much against it; and this lasted until I went to Oxford , where it would not be suffered. When at Oxford , I took up Law’s Serious Call, expecting to find it a dull book (as such books generally are), and perhaps to laugh at it. But I found Law quite an overmatch for me; and this was the first occasion of my thinking in earnest of religion after I became capable of rational inquiry.”

Edward Gibbon said: “If Mr. Law finds a spark of piety in a reader’s mind, he will soon kindle it into a flame.”

Law was not the messiah, and indeed Wesley ended up calling him a very naughty boy (for his increasing mysticism and theological drift), but what I want to point out in highlighting him is that God always finds a way to Shepherd his people no matter what the ecclesiastical authorities are doing.

The Nonjurors may have died out by 1805, but the fruit on their principled opposition to the prevailing winds in the established church lived on through William Law’s impact on Wesley, Whitefield, Wilberforce et al. This bit of history may give us pause to think about the likely longevity of breakaway movements (even when backed by an Archbishop of Canterbury), but it also gives us reason to trust that when we take a risk in seeking first his Kingdom, not counting the cost, that the Lord will always bring fruit from that.